This text is part of the Weather Preparedness & Resilience Toolbox developed by the YOUROPE Event Safety (YES) Group within YOUROPE’s 3F project (Future-Fit Festivals). It is aimed at everyone involved in planning, building, and operating open-air events. It helps festivals and other outdoor events become truly weather-ready by offering both practical and research-based resources as well as background information on weather and climate. Learn how to design safer and more weather-resilient outdoor events.

Introduction On Site Implementation

On-site implementation is the point where all planning, forecasts, and written procedures must translate into concrete behaviour, physical movement, and timely decisions on the festival site under real weather conditions.

It is the decisive phase in which all prior planning, risk assessment, monitoring, and decision-making are tested against reality. For outdoor festivals, weather-related risks do not materialise on paper; they materialise in mud, wind loads, heat stress, reduced visibility, delayed production schedules, fatigued staff, and crowds reacting emotionally under uncertainty. The quality of on-site implementation determines whether weather hazards remain manageable operational challenges or escalate into safety-critical situations.

For outdoor festivals, on-site implementation under changing weather is critical because:

- Weather impacts can evolve in minutes, while crowd movement and technical operations have inertia; decisions must anticipate this mismatch.

- Many control levers (sound, light, programme, bar service, transport, camping, social media) are dispersed across different organisations and contractors.

- This topic is often underestimated because “weather” is treated as a planning input (forecasts, generic contingency clauses) rather than a dynamic operational process that must be actively managed from first vehicle on site to last truck out. Teams tend to overestimate their ability to “handle it on the day”, underestimate the speed at which weather and crowd dynamics interact, and underestimate the friction created by fatigue, noise or alcohol,

If implementation fails, we risk seeing

- late reactions: stages not cleared, site not zoned, tents not lowered, or evacuation not started until weather impacts are already obvious on site.

- inconsistent actions: different gates, stages, or security teams applying different thresholds and messages, confusing crowds and undermining authority.

- implementation gaps: well-written severe weather plans that are not accessible, not rehearsed, or not translated into simple instructions, signage, and radio codes that crews actually use.

From a duty of care perspective, authorities and courts increasingly expect that organisers not only possess risk assessments and severe weather plans, but can demonstrate that on-site implementation is structured, trained, documented, and auditable. This includes at least:

- Defined roles for weather monitoring, decision-making, and operational command with documented triggers and actions.

- Proof that staff have been briefed, that drills or tabletop exercises occurred, and that critical decisions and timings were logged.

Key Principles

On-site implementation in adverse or rapidly changing weather rests on several applied concepts that must be understood before tools, checklists, and procedures can be used effectively. These concepts link meteorology, crowd science, and operational command into a coherent operating model for festivals.

Terminology

- Lead time: the time between a reliable indication that a hazardous weather impact is likely and the moment that impact affects the site. For festivals, practical lead time is what remains after internal decision-making, communication delays, and the physical time needed to move crowds and reconfigure infrastructure.

- Trigger–action logic: pre-defined, unambiguous links between measurable conditions (e.g. “lightning within 8 km”, “wind gusts > 20 m/s”, “heat index > 38 °C”) and operational actions (e.g. “stop show”, “lower PA”, “clear front-of-stage pit”, “start phased closure of bars”).

- Phased response: stepwise escalation of measures (e.g. prepare, pause, protect, evacuate) aligned with the severity and proximity of the hazard, designed to avoid binary “all or nothing” decisions and reduce last-minute improvisation.

- Dynamic residual risk: the risk that remains after actions have been implemented, recognising that weather and crowd states continue to change and that each intervention changes the risk landscape (e.g. shelter congestion, traffic queues, exposure of crews during rigging changes).

- Operational capacity: the actual ability of the site, staff, and infrastructure to carry out the planned actions within the available lead time, under realistic conditions of noise, darkness, intoxication, and fatigue.

Practitioners must explicitly distinguish between

- Technical triggers (e.g. measured lightning distance, radar signatures, forecast wind gust probabilities) and operational triggers (the point in time at which the organisation must act, backwards-calculated from evacuation and reconfiguration times).

- Planned capacity (in concepts and documents) and effective capacity in real time, which is impacted by absent staff, broken radios, blocked routes, or unexpected crowd distributions.

Important basics

- Time is a primary safety resource

- Time is consumed by monitoring, internal consultation, decision-making, communication, and physical movement.

- Lead times for weather must therefore be translated into site-specific maximum response times for each warning type and scenario.

- Front-line staff need short, clear instructions, standard radio phrases, and simple visual cues; complex plans must be pre-digested into checklists and playbooks.

- Pre-agreed thresholds and authority lines support faster, more consistent decisions under pressure.

- The safe movement of crowds takes predictable, non-negotiable time depending on density, route capacity, and behaviour.

Operational Relevance

On-site implementation must be understood as a continuous control loop, not a linear execution phase. Conditions change, assumptions degrade, and protective margins shrink over time. Implementation therefore requires permanent reassessment of whether operational reality still matches planning assumptions.

Risks only become manageable when they are translated into observable indicators and actionable thresholds. Abstract hazards such as “strong wind” or “heavy rain” must operationally for example be reframed as:

- load exceedance risk for temporary structures,

- ground bearing capacity reduction,

- reduced walking speed and increased slip probability,

- impaired visibility for staff and vehicle movements.

For temporary infrastructure, on-site implementation must address:

- Structural limits: stages, roofs, LED screens, temporary grandstands, tents, inflatables, and signage have defined wind, precipitation, and temperature limits that dictate when they must be secured, lowered, or cleared.

- Ground conditions: rain, mud, and flooding affect load paths, vehicle mobility, and slip/trip risk in escape routes, especially on slopes and temporary matting.

- Power and communication: storms, heat, or moisture can compromise generators, cabling, and wireless systems, exactly when clear communication is most needed.

Spatial layouts strongly influence implementation feasibility:

- Open fields with multiple wide exits allow faster dispersal but offer limited high-quality shelter against lightning or wind.

- Dense tent and stage fields with chokepoints and mixed uses (camping, vendors, stages) create complex movement patterns and high dependency on continuous wayfinding and steward guidance.

- Shelter strategy (hard buildings, car parks, robust tents, internal “safe zones”) must match expected crowd flows and lead times; otherwise, “seek shelter” instructions translate into uncontrolled crowd self-organisation.

Audience behaviour and crowd dynamics under weather stress introduce further complexity:

- Rain and cold compress crowds towards sheltered or warmer areas, increasing localized densities and potentially blocking routes or exits.

- Heat drives demand for shade, water, and slower movement; queues for resources can intersect with critical routes, complicating any later evacuation.

- Announcements that interrupt performances or restrict alcohol or stage access for weather reasons can trigger frustration, non-compliance, or attempts to circumvent controls, particularly when messages are unclear or inconsistent.

Staff performance and fatigue are decisive factors in on-site implementation:

- Long shifts, night work, adverse conditions, and high noise levels degrade perception, communication, and adherence to procedures.

- Weather responses often require the most complex coordination at the time when staff are already at peak fatigue (late evening, post-peak).europa+1

- Dedicated supervisors and floaters in high-risk zones, as well as a named weather monitor feeding supervisors, significantly improve implementation speed and coherence.

Production schedules and commercial pressure intersect with weather responses in several ways:

- Programming, artist expectations, broadcast windows, and vendor revenue create strong incentives to “hold the show” or “wait another 10 minutes”, eroding safety margins.

- Critical technical operations (rigging, changeovers, pyrotechnics) may coincide with deteriorating conditions, exposing crews and increasing the consequences of delays.

- On-site implementation must therefore include explicit authority and backing for safety-led decisions to pause, modify, or cancel, even where this conflicts with commercial targets.

If it goes wrong: Cause-Effect Chains

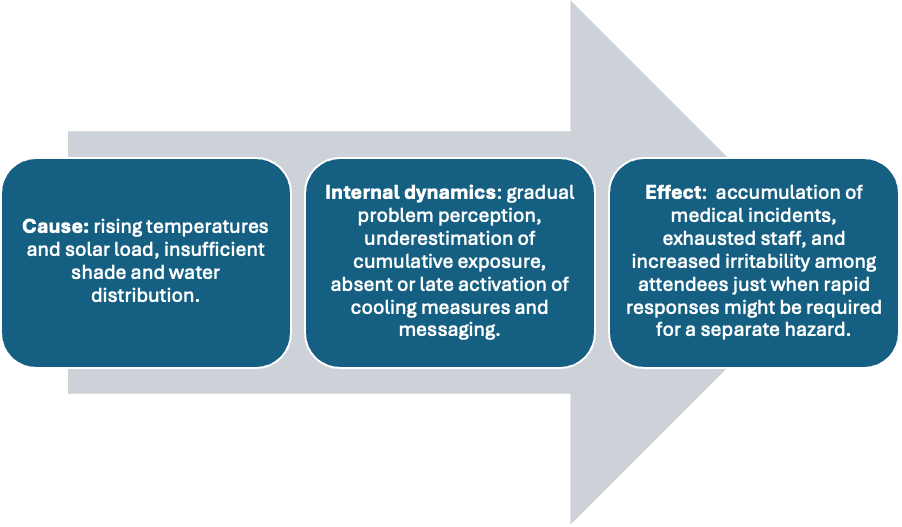

Weather-related risks at festivals emerge from dynamic interactions between meteorological evolution, site design, crowd distributions, and decision-making under uncertainty.

Understanding these cause-effect chains is essential to design triggers, lead times, and on-site procedures that prevent escalation and tipping points.

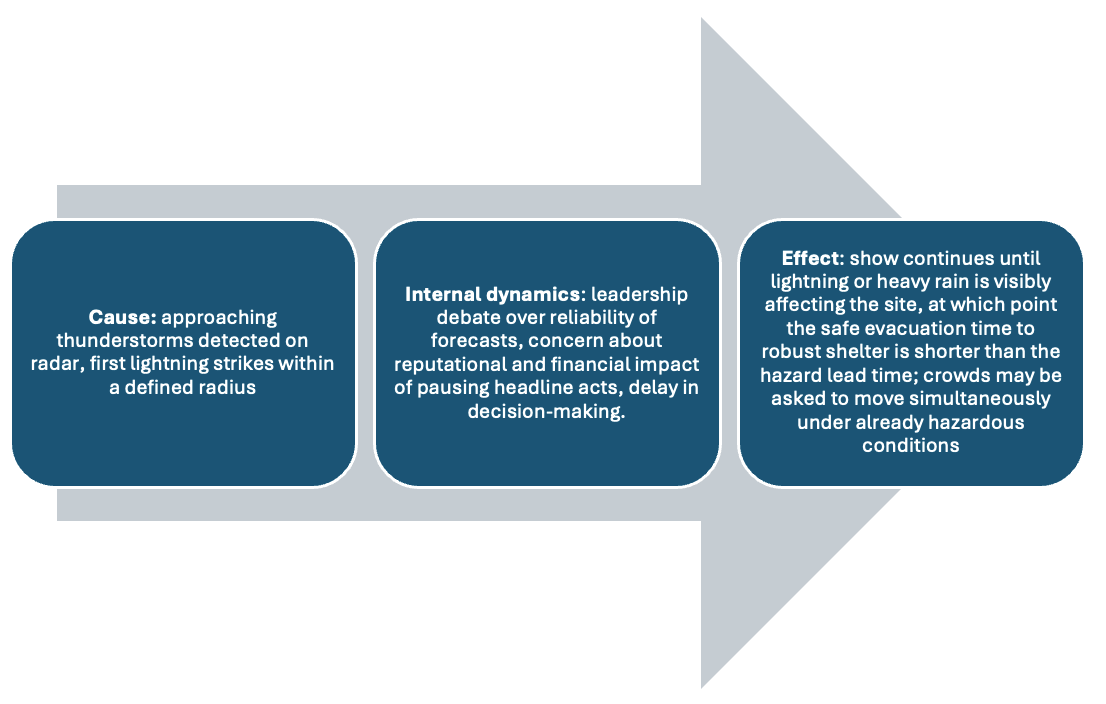

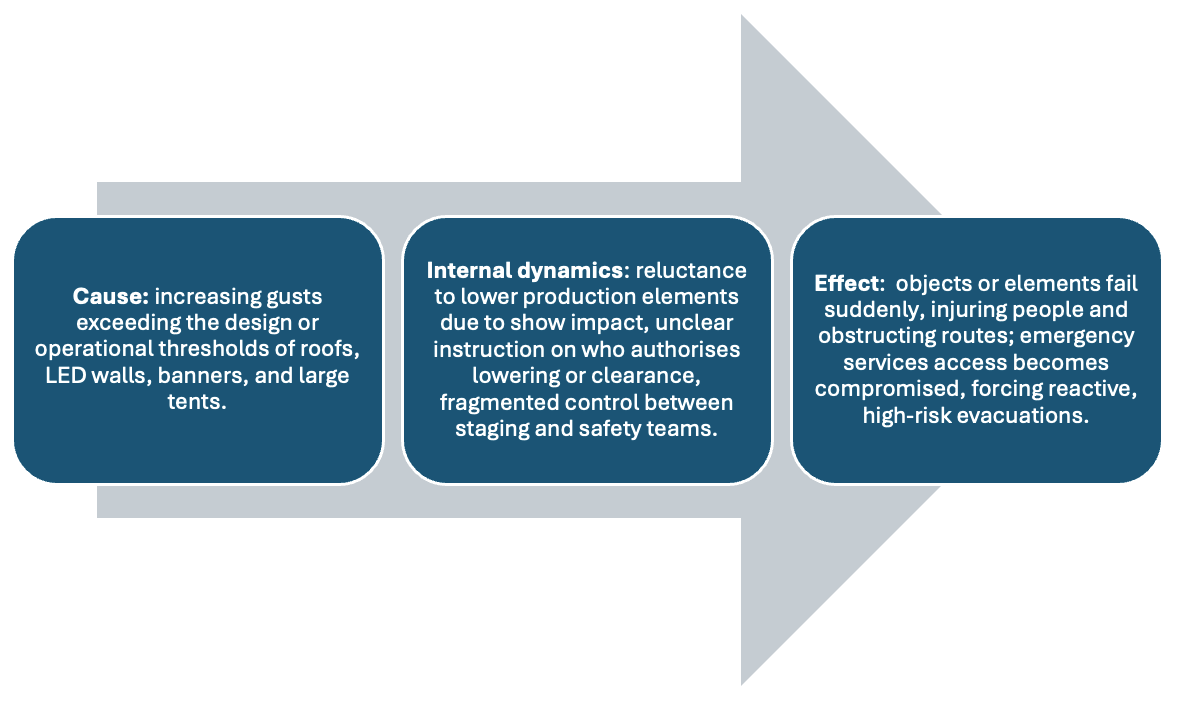

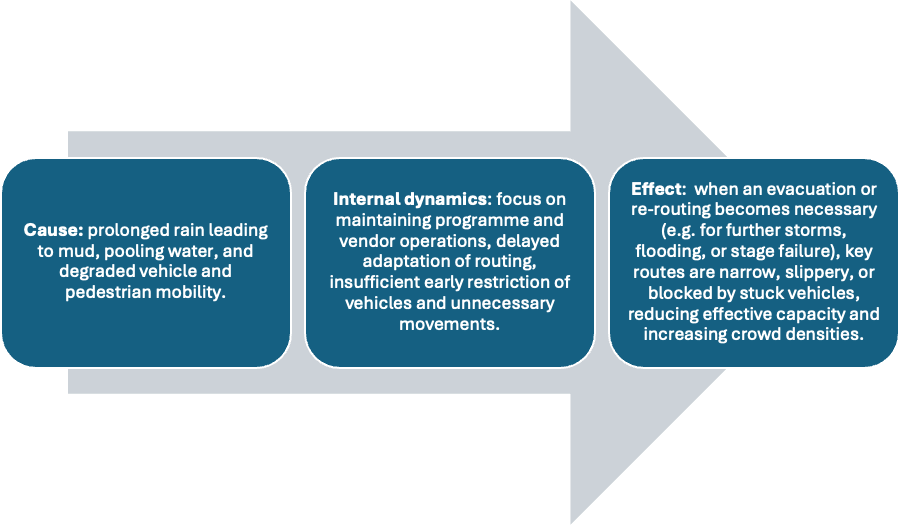

Examples for cause-effect chains due to a lck of proper on-site implementations could be:

Lightning approach

Wind gusts and temporary structures

Rain, ground degradation and escape capacity

- Heat, dehydration, and delayed decisions

Realistically, most consequential problem is the gap between the sophistication of planning documents and the practical simplicity required in the field.

More information

- https://www.weather.gov/media/dvn/NWSDVN_eventplanning_guide.pdf

- https://www.ticketfairy.com/blog/festival-weather-monitoring-and-alert-systems-how-to-keep-outdoor-events-safe

- https://www.weather.gov/media/crh/eventready/Event_Ready_Guide.pdf

- https://tseentertainment.com/common-safety-risks-in-outdoor-staging-tse-entertainment-event-safety-guide/

- https://kitec.com.hk/the-role-of-weather-in-event-planning-how-to-stay-ahead-of-unpredictable-conditions/

- https://www.eventsafetyinstitute.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/26172.pdf

- https://www.ticketfairy.com/blog/festival-risk-management-and-safety-planning-secrets-for-an-incident-free-event

- https://eventstaff.com/blog/outdoor-event-staffing-how-to-plan-for-weather-risks

- https://www.visualcrossing.com/resources/blog/outdoor-event-planning-for-unpredictable-weather-safer-smarter-venue-and-logistics-management/

- https://www.huntingdonshire.gov.uk/media/2746/hse-event-safety-guide.pdf

- https://eu.taf.cz/why-every-live-event-needs-a-weather-emergency-plan

- https://www.vfdb.de/media/doc/sonstiges/forschung/eva/tb_13_01_crowd_densities.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/org/science/article/pii/S1753833520000044

- https://esns.nl/en/conference/panels/when-the-show-cannot-go-on/

- http://rain-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/D3.3-Case-Studies.pdf

- https://safetydocs.org/post/festival-safety-planning-tool-for-hse-compliance-safety-docs

- https://csmsecurity.co.uk/the-ultimate-guide-to-festival-security-planning/

- https://xtix.ai/blog/building-weather-disruption-contingency-plans-for-european-festivals